Executive Summary

In 2020, Klaus Kraemer and colleagues published a representative survey of 2,000 individuals in Austria. Their findings were striking: across all groups, independent of age, gender, education, or income, most people knew little about the monetary system or its institutions. Widespread myths prevailed, such as the belief that money is still backed by gold [1]. For citizens, this knowledge gap may seem inconsequential. For leaders and decision makers, however, ignorance is highly consequential. We are living through a decisive monetary transition. Physical cash is being displaced by digital money. At the same time, centralized and decentralized monetary systems are beginning to compete. Decisions in the coming decade will shape not only financial stability, but also geopolitical dynamics.

The aim is not advocacy but clarity: to equip decision makers with the foundation to navigate a world where inflationary monetary systems coexist and compete with Bitcoin. This intelligence brief provides a concise, evidence-based overview of the essential features of today's monetary system and its tensions. It highlights surprising and underappreciated facts, traces how we arrived at the current design and examines the challenges of inflation, deflation and systemic fragility. It then considers how an alternative paradigm, embodied by Bitcoin, may reshape the link between technological progress and human prosperity.

Hard facts about money and our monetary institutions today

Since 1971, the world has operated on a global debt-based fiat monetary system. Fiat money derives its name from the Latin fiat ("let it be done") and functions as currency because governments declare and enforce it as legal tender.

Currency instability is systemic. Between 1970 and 2011, the world experienced no fewer than 147 banking crises, 218 currency crises and 66 sovereign debt crises [2].

Most people earn fiat money through labor, while its creation requires nothing more than a keystroke.

Fiat money is created through credit. When banks issue loans, they create new money ex nihilo, without relying on prior deposits [3, 4].

Central banks issue physical banknotes. However, over 90% of the money supply exists as digital bank deposits created by private bank lending, not backed by physical cash or coins [3, 4].

If all debts are repaid, almost no money would be left except cash and coins.

Inflation is a policy choice. Most central banks target an arbitrary annual 2% erosion of purchasing power, describing it as price stability [5, 6, 7].

Monetary control is indirect. Central banks can influence, but cannot precisely control, the total quantity of money in circulation.

How did we get here?

The story of money is often told in two competing ways: as a history of scarce commodities, or as a history of credit and state decrees. Both perspectives capture part of the truth and the dominating form depends on context. Within cohesive jurisdictions where trust and enforcement are reliable, credit ledgers tend to expand. Across borders or between strangers, trust is harder to maintain, and settlement in bearer assets like gold is preferred. History shows the oscillation between these two forms: ancient communities ran extensive credit systems but relied on commodity settlement when interacting with outsiders or when ledgers and trust in institutions failed.

Technology has continually shaped this balance. Banking introduced the separation between fast transactions and slower settlement. Instruments such as paper notes and double-entry bookkeeping allowed trade to expand “on credit,” with only occasional metal settlement. In the nineteenth century, the telegraph introduced a decisive break: ledgers could be updated almost at the speed of light across continents, while gold still travelled at the speed of ships. This speed gap encouraged further abstraction, centralized clearing, and larger-scale credit expansion. The physical constraints of gold made it less relevant for day-to-day commerce, even if it remained the ultimate backstop.

The twentieth century institutionalized this shift away from gold. The Bretton Woods system of 1944, established after the Second World War, pegged major currencies to the U.S. dollar, which itself was convertible into gold. The arrangement stabilized global trade for a generation but concentrated trust and power in U.S. policy. Growing U.S. deficits incurred through infrastructure programs and wars, alongside the global demand for dollars, strained the system until the “Nixon shock” of 1971, when the United States suspended gold convertibility. What was presented as temporary became permanent.

By suspending gold convertibility, the United States severed the final link between money and commodity anchors, ushering in the current era of purely fiat currency. In this new global architecture, sustained only by trust in institutions, the petrodollar system preserved international demand for dollars while central banks and governments gained full discretion over the money supply of their respective currency monopoly. This shift also solidified the role of commercial banks as the primary creators of money through credit. The fifty-plus-year fiat experiment has brought financial innovation, globalization and an increase in living standards, but has also been marked by recurring crises, systemic fragility and unsustainable imbalances.

Five decades post-gold standard

The fiat era quickly revealed its fragility. Between 1970 and 2011 the world experienced 147 banking crises, 218 currency crises, and 66 sovereign debt crises [2]. Such figures highlight that financial instability is not an anomaly but a recurring feature of the system. Cycles of credit booms and busts, currency devaluations, and sovereign defaults became embedded in the architecture of global finance, along with social consequences ranging from widening inequality to political polarization.

Financialization amplified these dynamics. From the 1980s onward, deregulation and liberalized capital markets encouraged greater leverage, speculative finance and the proliferation of complex derivatives. Much of the created liquidity was directed into financial assets, not toward productive investment. Asset price inflation, in equities and in real estate, became a recurring outcome. The benefits of monetary expansion were unevenly distributed. Those closest to money creation and money influx, such as financial institutions and asset holders, gained disproportionately, while wage earners and savers, handling mainly/only fiat currency, often bore the costs through inflation and crisis fallout.

The instability was not confined to advanced economies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, originally designed under Bretton Woods, assumed new roles in the fiat era. The IMF increasingly acted as crisis manager and lender of last resort to sovereigns, especially in Latin America during the 1980s debt crisis, in Africa through structural adjustment programs, and in Asia during the 1997 financial crisis. Assistance was typically provided under strict conditionality: fiscal austerity, privatization and structural reforms aimed at restoring debt service for industrialized nations. The World Bank, meanwhile, expanded its role as a development financier. Infrastructure and modernization projects were funded through dollar-denominated loans that deepened many countries’ exposure to the global credit cycle. Together, the IMF and World Bank reinforced the centrality of the dollar-based system and the asymmetry between creditors and debtors. Nations in the Global South often found themselves locked into cycles of borrowing, crisis, and restructuring. A new form of colonialism in which debt became the chains was born [8].

Central banks in advanced economies responded to each crisis by intervening ever more aggressively. Lower interest rates, large-scale liquidity injections and eventually quantitative easing became the standard tools of crisis management. Bailouts socialized risks and losses while profits were privatized. One example where this became obvious even to the public was the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Debt levels ratcheted up with each cycle, leaving the global system more leveraged and increasingly dependent on monetary accommodation.

Today, the debt cycle has reached the level of the state itself. Sovereign debt in advanced economies has climbed to unprecedented levels, leaving governments dependent on low interest rates to finance themselves. This creates a new regime of fiscal dominance, in which central banks are constrained by fiscal realities. Raising rates to fight inflation risks triggering sovereign debt crises; keeping rates low risks entrenching inflation and asset bubbles. The United States illustrates this dilemma. Federal debt now exceeds $37 trillion, and debt service costs are among the fastest-growing components of the budget. By 2024, federal interest payments alone reached nearly $1 trillion annually, roughly equivalent to the country’s military budget. Hence, monetary tightening can no longer be assessed solely by its effects on labor market or inflation, it directly threatens fiscal sustainability. The dilemma is not confined to the United States. In Europe and Asia, where sovereign debt levels are also elevated, central banks face the same tension between price stability and fiscal sustainability. In this environment, monetary authorities risk becoming instruments of government finance rather than independent stewards of monetary stability.

Inflation versus deflation

The instability of the fiat era has been managed not only through crisis interventions but also through a persistent bias in favour of inflation. Inflation is not an accident of monetary policy failure; it is a structural necessity. In a system built on ever-expanding credit, monetary devaluation, experienced by households as rising prices, eases the real burden of debt and helps finance growing deficits.

Central banks formalised this bias by defining “price stability” as a controlled erosion of purchasing power. Most advanced economies try to target an arbitrary annual inflation rate of about 2% [5, 6, 7]. In other words, money is designed to lose value year after year. A dollar, euro, or yen today will buy less a decade from now. This programmed devaluation is defended as a safeguard against deflation and as a way to encourage spending rather than saving. But calling rising consumer prices “stability” obscures what is really being stabilised: a debt-based monetary system that necessitates devaluation to survive.

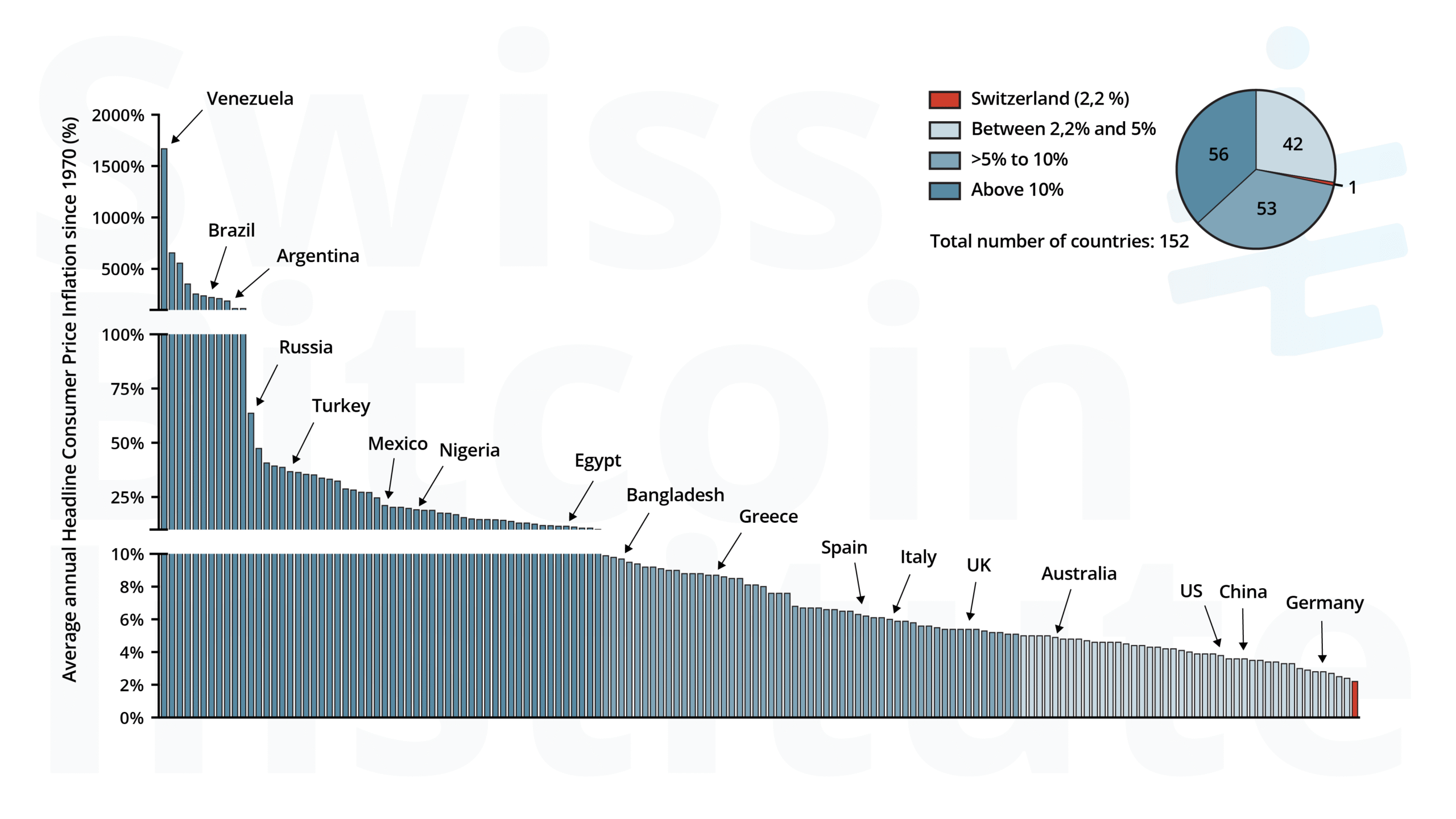

Figure 1: Average annual inflation of 152 countries since 1970. Since the end of Bretton Woods, no country has averaged less than 2% inflation. Switzerland, at 2.2%, comes closest. 42 countries have averaged between 2,2% and 5%; 53 greater than 5% and up to 10%; 56 countries above 10%. Source: World Bank, A Global Database of Inflation, 2025 [9].

Today’s money is mostly created through credit, meaning it comes into existence when banks issue loans [3, 4]. These loans must be repaid with interest, which introduces a systemic demand for more money than was originally created. That interest can only be paid back either by drawing from the existing money supply in the economy, or through the issuance of new interest-bearing loans, which expand the money supply and perpetuate the cycle.

This dynamic creates a system that cannot, by design, repay all debts without either exhausting the money supply or relying on continual credit expansion.

Deflation poses a direct threat to such a system because it increases the real value of debt. A simple example illustrates the point: if you take out a $10,000 loan to buy a car, and inflation is running at 2% per year, that loan becomes easier to repay over time. But if deflation is running at 2% per year, the opposite happens: your debt burden becomes heavier in real terms. Scaled up across firms, banks and governments, the result is systemic fragility. A highly leveraged system cannot remain solvent without continual credit expansion, which is why deflation is correctly treated as an existential threat for a debt-based monetary system.

And yet, in a competitive market, prices have the natural tendency to fall. Human curiosity drives technological innovation, which raises efficiency and pushes costs down. Competition ensures these gains are passed on to consumers. From agriculture to manufacturing to electronics, progress has historically translated into lower prices. Deflation, in this sense, is not an anomaly but the normal expression of efficiency gains in competitive markets. To claim that a competitive market-based economy requires permanently rising prices is to misunderstand or misinterpret its fundamental mechanism.

Mainstream economics nonetheless portrays deflation as destructive, warning that falling prices would cause consumers to delay purchases, grinding the economy to a halt. But this fear is overstated. In practice, deflation does not paralyze consumption. It may alter the timing of some purchases, but essential spending and investment generally continue. We see this clearly in today’s technology sector: people regularly buy phones, TVs, laptops and other devices despite knowing they will be cheaper and potentially better next year.

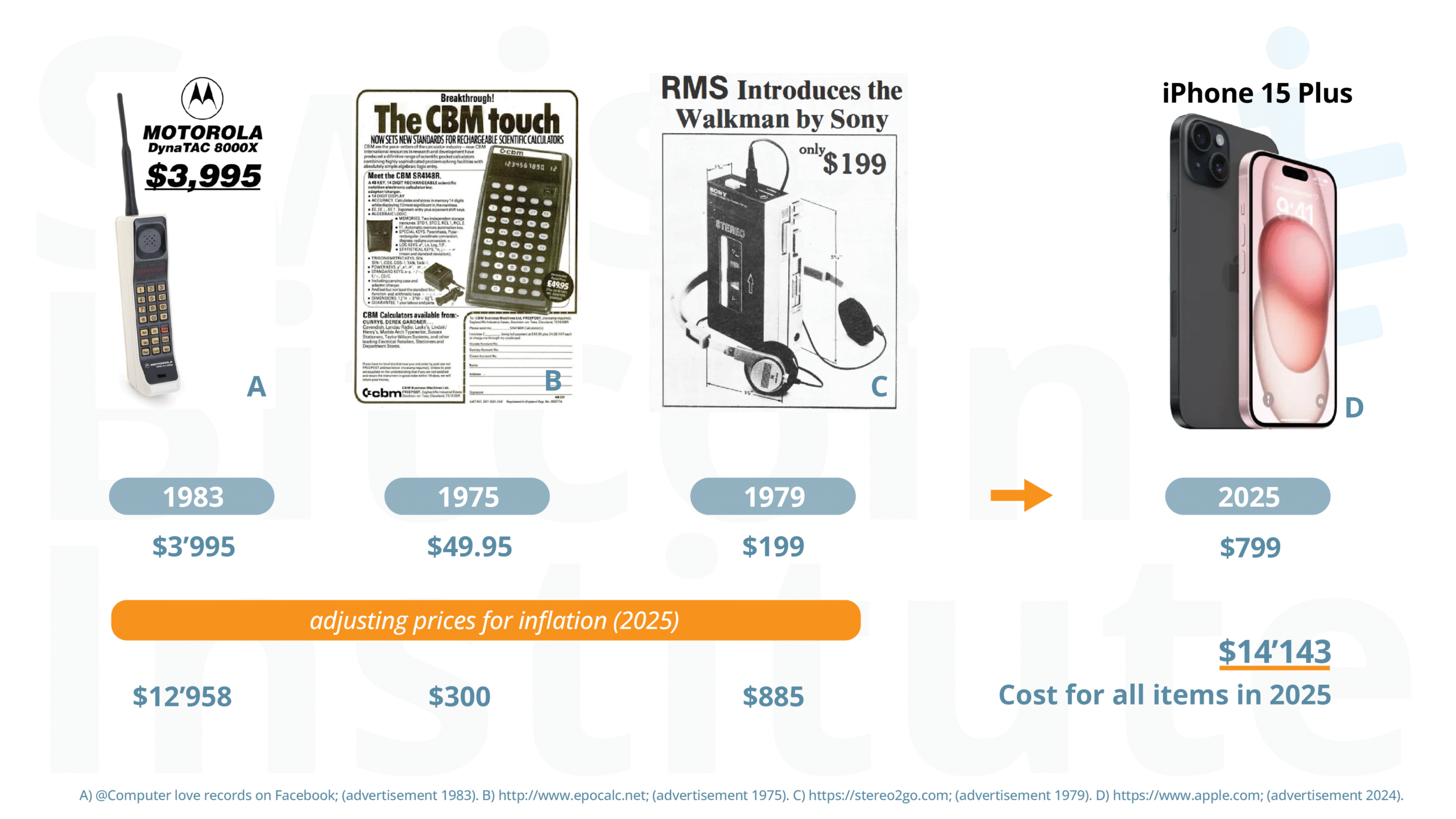

Figure 2: Technology's deflationary effect: more value for less. Representative historical examples of consumer electronics showing that technological progress drives prices down while functionality improves.

What holds true for modern technology has precedent in broader economic history. Periods of deflation under a market-based gold standard, such as during the late 19th century, coincided with groundbreaking innovations, rising productivity and higher living standards [10, 11, 12, 13]. The idea that falling prices are a threat to a competitive market-based economy does not hold up under scrutiny [13, 14, 15]. Empirical research confirms this: Atkeson and Kehoe (2004), studying data from 17 countries over more than a century, found no systematic relationship between deflation and depression [15]. The notable exception is the Great Depression, but here deflation was the symptom rather than the cause. The crisis was preceded by a tremendous credit expansion during the “roaring twenties,” leaving the system highly leveraged. When the bubble burst, debts became unserviceable in real terms, and the monetary system was not re-inflated. This debt-deflation dynamic, described by Irving Fisher (1933) and later expanded by Friedman, Schwartz, and Bernanke, explains why that episode was so severe [16, 17, 18].

The inflation versus deflation dilemma will likely intensify. Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics promise to radically reduce production costs, automate labor and increase efficiency across industries. These forces should lead to falling prices and greater abundance. But in a system that requires persistent inflation to remain solvent, such deflationary pressures are not welcomed. They are problems to be offset. Central banks will thus be compelled to counteract these efficiency gains by incentivising credit creation and injecting liquidity. In effect, we are creating money to fight the falling prices brought about by progress, all while eroding the value of existing savings and pushing debt levels ever higher. The result is a kind of treadmill economy: we must run faster, accumulating more debt and creating more currency, just to stand still.

Some argue that we can “grow out” of our debt burden by increasing the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Still, at its core, most increases in GDP leverage technology to increase productivity. Therefore, genuine economic “growth” mostly reinforces the very deflationary forces that the system is designed to resist.

We are left with a profound paradox: the fiat system depends on inflation, yet the engines of modern progress and competitive markets generate deflation. This contradiction raises fundamental questions about the long-term viability of the current monetary architecture and opens the door to speculating what a world might look like if individuals were allowed to benefit from technological deflation, rather than be shielded from it by monetary policy.

The following quotes (curated by Lyn Alden in her book "Broken Money" [19]) illustrate how central bankers themselves make clear that monetary policy is designed to prevent deflation from occurring:

James Bullard (Federal Reserve) made this clear in 2013: "If inflation continues to go down, I would be willing to increase the pace of purchases." A year later, he reiterated: "I have been concerned about low inflation… There hasn't been much indication so far it is moving back toward target."

Janet Yellen (Federal Reserve), at her final press conference as Chair in late 2017, stressed that her greatest regret was failing to lift inflation to the Fed's mandate: "We have a 2 percent symmetric inflation objective. For a number of years now, inflation has been running under 2 percent, and I consider it an important priority to make sure that inflation doesn't chronically undershoot our 2 percent objective."

Christine Lagarde (European Central Bank) carried the same theme to her confirmation hearings in 2019: "The euro area economy faces some near-term risks… and inflation remains persistently below the ECB's objective. I therefore agree… that a highly accommodative policy stance is warranted for a prolonged period of time in order to bring inflation back to 'below but close to 2%.'"

Haruhiko Kuroda (Bank of Japan) echoed the same doctrine in, ruling out any exit from negative rates (Reuters, 2018): "They [negative rates] are necessary to accelerate inflation to [the] 2 percent inflation target."

Essential features of deflation-permitting money

To permit deflation to pass through globally, money must have certain features:

- Credibly capped supply: no discretionary debasement; issuance must be rule-bound and predictable.

- Neutrality and openness: no privileged issuers or regions; anyone can hold, verify and settle.

- Settlement finality at scale: a way to make and verify final settlement globally without trusted intermediaries.

- Censorship resistance and self-custody: users can hold and transfer value without permission from central gatekeepers.

- Auditability and verifiability: any participant can independently verify supply and their own balances.

- Portability, divisibility, durability: money must be easy to move, split and secure across borders and time.

By design, contemporary fiat money lacks the first criterion (supply discretion) and relies on a centralized trust stack for the rest. Bitcoin is the only live system today that plausibly meets all six criteria. It combines a hard cap (21 million) with an open, permissionless settlement network secured by proof-of-work (PoW), globally auditable state, high portability and divisibility (satoshis), and credible resistance to debasement or capture so long as decentralisation and security are preserved.

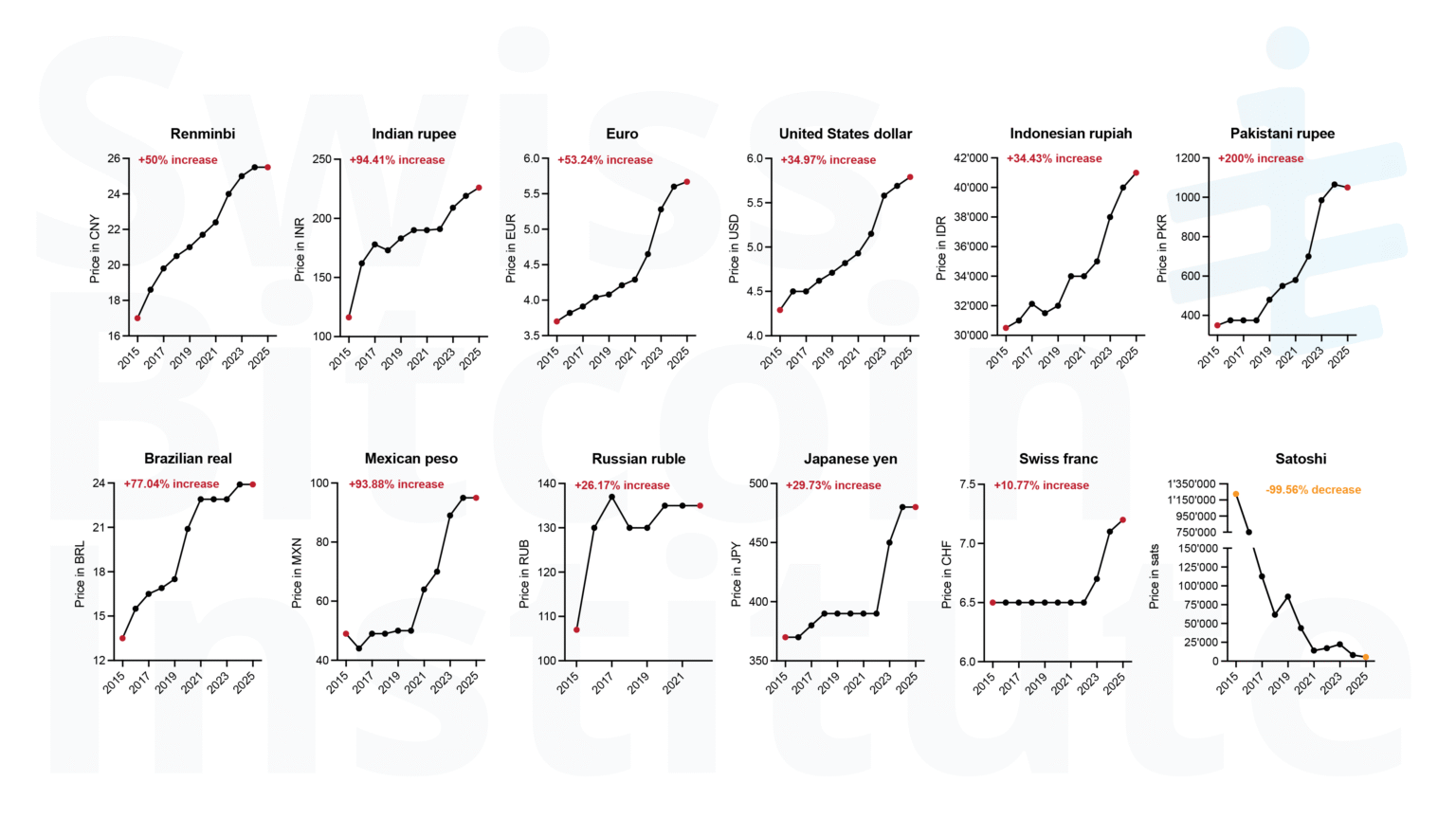

Figure 3: Big Mac price development in fiat currencies and Bitcoin (2015-2025). Annual Big Mac prices (2015-2025) are shown in local currencies for the ten largest currency zones by population represented in The Economist Big Mac Index (July data preferred, January otherwise) [20], with the Swiss franc (CHF) added for institutional relevance. The set includes CNY (China), INR (India), EUR (euro area), USD (United States), IDR (Indonesia), PKR (Pakistan), BRL (Brazil), MXN (Mexico), RUB (Russia, data until 2021), JPY (Japan). NGN (Nigeria) and BDT (Bangladesh) would normally qualify by population but are not in the dataset. Bitcoin prices (1 BTC = 100,000,000 sats) are shown as the number of satoshis (sats) needed to buy one Big Mac. To calculate this, the annual average BTC/USD price was used to determine how many sats equal one USD, and this was multiplied by the Big Mac's USD price.

A counterfactual world of technological deflation

The following scenarios are necessarily speculative. They do not aim at completeness, but illustrate selected domains where the consequences of a deflation-permitting monetary order may be most visible. To make this tangible, the analysis proceeds from the individual to the firm, then to the state, and finally to the international system.

Deflation-permitting money would transform daily economic life. Savings and retirement planning would no longer depend on channelling household wealth into financial products simply to preserve value. A unit of money set aside in early adulthood could reliably purchase more goods and services decades later. Wages would also take on a new character: with prices falling, real wages rise even if nominal wages are flat, giving workers a tangible increase in purchasing power. Over time, however, employers under pressure from rising real wage costs may seek nominal adjustments downward. Consumption patterns would also shift. Appreciating money raises the opportunity cost of impulsive purchases, encouraging households to prioritise durability and quality over volume. Repair services and secondary markets would expand, while business models built on planned obsolescence would find it harder to survive. Waste streams would shrink, product lifespans would lengthen, and resource throughput would slow. Housing markets would also correct: without the monetary premium that today turns property into an inflation hedge, prices would align more closely with utility value. Homes would be more affordable and speculative bubbles less extreme.

For firms and markets, the absence of cheap credit would fundamentally reshape capital structures. Debt becomes riskier when repayment must be made in money that gains value, encouraging companies to finance themselves more through equity and retained earnings. Leverage would fall, and the financial sector as a whole would shrink in scale but deepen in quality, as capital would be allocated to projects with demonstrable productivity gains rather than speculative arbitrage. Entrepreneurship would continue, but under sharper discipline: ventures would need to demonstrate genuine efficiency improvements to attract funding, while “spray and pray” investment strategies would recede. Banks, stripped of their ability to create money ex nihilo, would return to narrower and more transparent functions: custody and risk management. Lending would persist, but closer to a full-reserve model in which loans are backed more strictly by deposits. In effect, the business landscape would be one where finance is a service to production, not the other way around.

States and public institutions would also be reshaped. Central banks, deprived of their traditional levers of discretionary monetary policy, would see their roles vanish or transform into primarily analytical and supervisory agencies, perhaps retaining responsibility for managing national reserves. The shift would resemble the fate of postal services after the rise of email: the core function becomes obsolete, while peripheral roles remain. Public finance would become more transparent as the inflation tax disappears, forcing governments to rely directly on taxation. Deficits would still be possible, but without the cushion of debasement their costs would be more immediate and visible. Social promises such as pensions would need to be funded in advance, making intergenerational trade-offs clearer. The capacity to finance wars and crises would change as well. Historically, emergencies have been met with borrowing and monetary expansion; under a deflation-permitting money, states would need to build reserves, tax openly, or issue voluntary bonds. Such constraints would make major interventions more transparent and politically accountable.

At the international level, a neutral global money would eliminate much of today's foreign exchange volatility, lowering the costs of trade and investment across borders. Smaller, less industrialised nations would no longer face chronic currency depreciation or capital flight. At the same time, the productivity gains of industrialised nations would diffuse globally: a technological breakthrough in one economy would translate into lower global prices, raising the purchasing power of holders of the money everywhere. This would represent a historic broadening of who benefits from innovation, turning deflationary progress into a shared dividend. The hegemonic position of the U.S. dollar would weaken, with strategic power shifting instead to the control of infrastructure and access to reliable, cheap energy. If settlement is secured through PoW, energy-rich states could gain leverage, making energy diplomacy as important as monetary diplomacy. Finally, with a stable unit of account, ecological and resource costs would be harder to obscure through monetary inflation. Price signals would reflect real scarcities more directly, aligning economic activity more closely with planetary resources.

Of course, these scenarios remain speculative and would not come without challenges. The path of transition is highly uncertain, more like a black box than a clear sequence. Downward wage adjustments, though more palatable in a context of rising purchasing power, remain psychologically difficult. Early adopters of deflation-permitting money gain disproportionate advantages, raising distributional concerns. Volatility in the adoption phase creates frictions for households and firms. Investment volumes may decline as debt financing becomes less attractive. It should also be acknowledged that a money supply which can be expanded quickly provides states with a powerful tool to respond to crises, wars or emergencies. This capacity for rapid, top-down mobilisation of resources is deeply embedded in the existing system and few governments would willingly give it up. States, institutions and individuals benefiting from today’s inflationary regime will therefore resist change, unwilling to forfeit both power and monetary sovereignty.

Yet taken together, this counterfactual illustrates a striking possibility: a monetary system that allows technological deflation to be broadly shared could rewire incentives across all levels of society. The question for decision makers is whether such a system—already emerging in parallel through Bitcoin—should be resisted, adapted to, or actively prepared for. For many, even a partial step into this deflationary reality may prove worthwhile.

Conclusion

The fiat system we are living in is structurally inflationary, requiring continual devaluation to sustain its debt-based architecture. By contrast, technology and competitive markets are inherently deflationary. This clash will exacerbate the instability of our current monetary system. Bitcoin, with its fixed supply and decentralized design, demands awareness of a potential paradigm shift in which individuals and societies directly benefit from technological deflation. While the hypothetical of a global monetary system, which allows for deflation, is speculative and the transition would be accompanied by many difficulties, its key features plausibly promise a notable alternative: savings that hold value, finance that serves production, public budgets that are transparent and innovations whose benefits are shared more broadly. For decision makers, the task is understanding. A hybrid world is already emerging: those tied to fiat will continue to live with inflation, while those using Bitcoin may continue to experience deflation. Leadership requires preparing for that coexistence and recognising that the greatest risk lies in ignoring it.

References

- Klaus Kraemer, Luka Jakelja, Florian Brugger and Sebastian Nessel: Money Knowledge or Money Myths? Results of a population survey on money and the monetary order. Cambridge University Press, 2020. Link.

- Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia: Systemic Banking Crises Database: An Update. IMF Working Paper 12/163, 2012. Link.

- Bank of England: Money creation in the modern economy. Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1. Link.

- Richard A. Werner: Can banks individually create money out of nothing? The theories and the empirical evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 2014. Link.

- Neil Irwin: Of Kiwis and Currencies: How a 2% Inflation Target Became Global Economic Gospel. The New York Times, 2014. Link.

- ECB press release: ECB's Governing Council approves its new monetary policy strategy. 2021. Link.

- Federal Reserve's Official Website (Board of Governors): The Federal Reserve seeks to achieve inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE). 2024. Link.

- Alex Gladstein: Hidden Repression: How the IMF and World Bank Sell Exploitation as Development. Bitcoin Magazine Books, 2023.

- Jongrim Ha, M. Ayhan Kose and Franziska Ohnsorge: One-stop source: A global database of inflation. Journal of International Money and Finance, 2023. Link.

- Thomas L. Hogan: How Good Was the Gold Standard? AIER Sound Money Project Working Paper, 2021. Link.

- Michael D. Bordo, John Landon Lane and Angela Redish: Good versus Bad Deflation: Lessons from the Gold Standard Era. NBER Working Paper, 2004. Link.

- Michael D. Bordo and Andrew J. Filardo: Deflation in a Historical Perspective. BIS Working Paper, 2005. Link.

- Claudio Borio, Magdalena Erdem, Andrew J Filardo and Boris Hofmann: The costs of deflations: a historical perspective. BIS Quarterly Review, 2015. Link.

- Michael D. Bordo and Angela Redish: Is Deflation Depressing? Evidence From the Classical Gold Standard. Cambridge University Press, 2009. Link.

- Andrew Atkeson and Patrick J. Kehoe: Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link? American Economic Review, 2004. Link.

- Irving Fisher: The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Econometrica, 1933. Link.

- Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz: A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton University Press, 1963. Link.

- Ben S. Bernanke: Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression. The American Economic Review, 1983. Link.

- Lyn Alden: Broken Money: Why Our Financial System is Failing Us and How We Can Make it Better. Timestamp Press, 2023. Link.

- The Economist: Big Mac Index, 2025. GitHub.