1. Monetary Competition Is Back

Why are central banks rushing to develop digital currencies (CBDCs)? Why are global corporations exploring stablecoins, and why are BRICS nations considering a new reserve currency? The answer is that for the first time in decades, the monetary landscape is becoming competitive again.

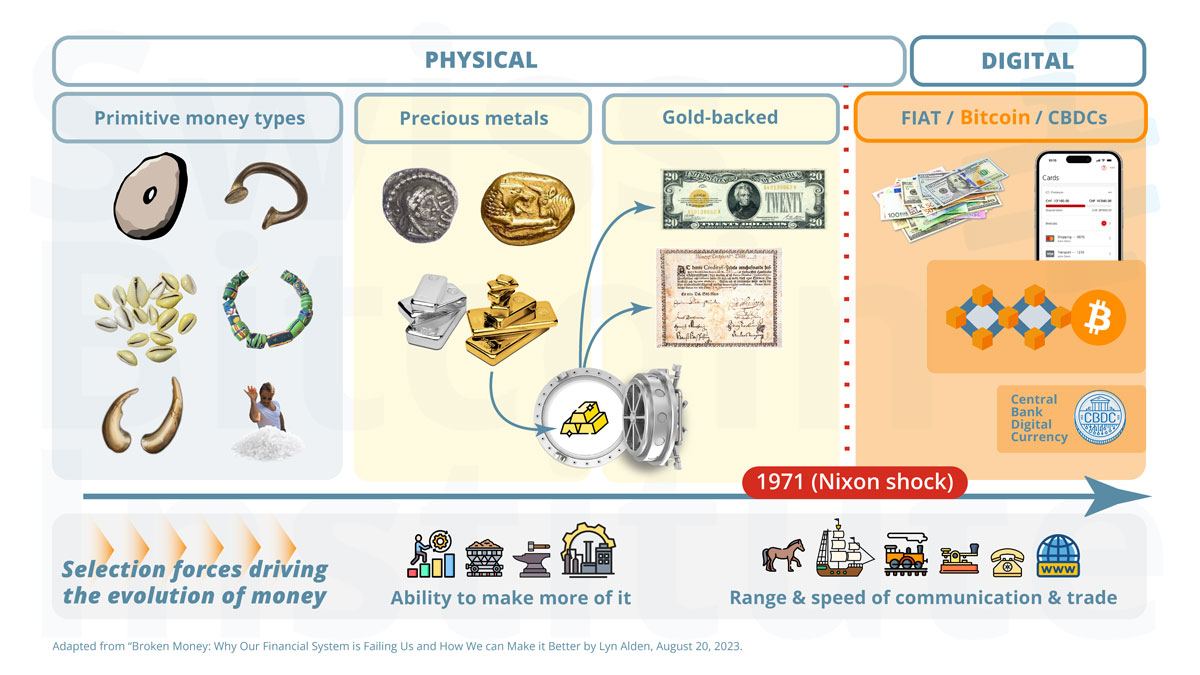

For the last several generations, we have lived in a monoculture of fiat currency. However, the emergence of Bitcoin has reopened the design space, triggering a "Cambrian explosion" of monetary experimentation. Today, fiat currencies and emerging digital alternatives are competing for adoption in a long sequence of monetary designs. The monetary landscape is no longer static; it is a contested environment where policy choices and institutional frameworks act as active selection pressures.

To understand which forms will survive and which will go extinct, we need more than a chronological list of events; we need to understand the mechanism of survival.

Money isn't random; it evolves. While often viewed as a mere social convention, history reveals a rigorous selection process where monetary systems behave similar to evolving species. They compete for adoption, and their survival depends on their "fitness": how well their design traits align with the technological and socioeconomic environment.

This intelligence brief traces the evolution of money through two major historical bottlenecks that defined our current system:

• The crisis of scarcity: Precious metals outcompeted early commodity monies because they remained scarce even as technology improved.

• The crisis of speed: As telecommunication accelerated the speed of commerce, physical gold lost its fitness and was replaced by the faster, more adaptable phenotype of fiat currency.

Today, we face a new inflection point. Different digital monetary designs are continuously tested against human needs, technological innovation, and institutional arrangements. Understanding the "selection pressures" of the past helps us identify the traits that will define the money of the future.

Figure 1: illustrates the evolution of money from physical forms to digital forms, highlighting the transition from commodity monies to precious metals to gold-backed currencies, and finally to fiat currencies and emerging digital alternatives like Bitcoin and CBDCs.

2. How an Evolutionary Biologist Would Look at Money

To analyze the current competition systematically, we can apply a "Darwinian lens" to money. Much like biological evolution, monetary evolution is not random; it follows three core principles:

• Variation: Societies constantly experiment with different money types, from ancient ledger systems, to shells, to digital numbers on a screen.

• Selection: Users and societies choose which money to hold and accept. Designs that solve problems are selected for; those that fail are selected against.

• Inheritance: Successful traits are copied and embedded into new monetary systems.

The monetary phenotype: In biology, a "phenotype" is the observable characteristics of an organism; like the protective shell of a tortoise or the locomotory efficiency of a cheetah. Applying this concept to money, the "monetary phenotype" is the bundle of traits that determines how a money functions. This includes its scarcity, fungibility, portability, verifiability, divisibility and resistance to censorship.

The monetary fitness: In biology, "fitness" is not about strength, but its match to the environment; essentially, how effectively an organism survives and propagates in a specific environment. Applying this concept to money, a monetary system is fit and able to propagate if it effectively performs three core functions for its users:

-

Unit of Account (UoA): A denominator for pricing.

-

Medium of Exchange (MoE): A means for settling transactions.

-

Store of Value (SoV): A way to preserve purchasing power over time and space.

Environments do not "choose," they filter. As the environment changes, through technology or changing socioeconomic dynamics, the traits required for fitness change. This explains why money evolves.

3. Two Evolutionary Bottlenecks Money Had to Overcome in Its Evolution

History reveals two major "bottlenecks" where selection pressures forced a convergence toward a dominant monetary phenotype.

3.1 First Bottleneck: The Crisis of Scarcity

Early monetary history was a period of intense variation. Societies experimented with diverse monetary phenotypes, from ancient ledger systems, to shells and beads, to tobacco and stones. As detailed by Lyn Alden in her book Broken Money, while these systems functioned well in closed environments, they reveal a consistent pattern of extinction: monies whose scarcity relied on primitive technology collapsed when faced with industrial innovation [1]. The following representative case studies from her book illustrate this first bottleneck.

Case study A: the wampum collapse

Indigenous nations and early colonists used polished shell beads (wampum) as a medium of exchange. Wampum had a high "stock-to-flow" ratio because drilling shells with stone tools was labor-intensive. When Europeans introduced industrial metal drills, the cost of production plummeted. Dutch and English manufacturers began mass-producing wampum, flooding the market. The supply became highly elastic, destroying its scarcity and rendering the monetary phenotype unfit.

Case study B: the inflation of rai stones

The island of Yap used massive limestone discs (rai stones) as a ledger of value. Because the stones had to be quarried on distant islands and transported by canoe, new supply was naturally constrained by the danger of the journey. In the late 19th century, Western traders (notably David O'Keefe) arrived with modern ships and explosives. They could quarry and transport stones with industrial ease. The supply of stones exploded. The monetary system suffered a crisis of provenance, eventually forcing the community to distinguish between "authentic" (scarce) stones and "O'Keefe" (easy) stones. The ledger was corrupted by technological ease.

These extinctions highlight why precious metals became the dominant global standard. Unlike shells or stones, gold possesses a unique geological trait: it is chemically impossible to synthesize. Even with modern industrial mining technology, humans cannot increase the above-ground gold supply by more than ~1.5% to 2% annually. Geology provided the "difficulty adjustment" that wampum, Rai stones and other commodity monies lacked.

3.2 Second Bottleneck: The Crisis of Speed

As societies industrialized, the environment changed again. The decisive new selection pressure was speed. For most of history, commerce moved at the speed of physical transport. The telegraph broke this link, allowing information to move at the speed of light while gold still moved at the speed of matter. To bridge this gap, society adopted a layered system: gold sat in vaults, while paper claims (banknotes and ledgers) circulated, preserving gold's scarcity while abstracting away its physical limitations.

However, this "claims on gold" system became fragile. Governments and banks issued more claims than there was gold (fractional reserve), leading to runs and crises. In the 20th century, notably in 1971, the link to gold was severed completely. While famously announced as a 'temporary' suspension, this makeshift adaptation hardened into the permanent genetic code of the modern financial system [2]. Gold's phenotype was no longer fit for a near instant telecommunication-based global economy.

3.3 The Winning Phenotype: Fiat Money

The winner of this second bottleneck was fiat money. Fiat can be defined as a sovereign ledger monetary system: a unit issued and governed by a state that is not redeemable for a scarce commodity, and whose monetary use rests on legal frameworks, institutions and fiscal capacity. The trait bundle of fiat currencies typically consists of:

• State enforcement and legal tender status: Fiat money is embedded in law. Governments designate it as legal tender (i.e., the unit that must be accepted for settling certain obligations), and regulators enforce contracts, accounting standards, and payment finality in that unit.

• Tax-driven baseline demand: A decisive fitness advantage of fiat is that taxes and other public dues are denominated in and settled with the sovereign unit. This creates structural demand even when voluntary monetary preference might be weak.

• Dematerialisation and ledger efficiency: In modern economies, fiat largely exists as ledger entries rather than physical cash. Most broad money takes the form of bank deposits created through commercial-bank lending within a regulatory and central-bank backstop framework.

• Elastic supply and discretionary issuance: Unlike commodity money, fiat has no "geological" production constraint.

• Credit-based money creation: The modern fiat system is coupled to credit. Expansions and contractions of bank balance sheets shape the effective money supply, while central-bank policy influences the price (interest rates) and availability of liquidity.

• Central-bank backstops and crisis governance: Central banks can act as lenders of last resort to the banking system and have repeatedly expanded their crisis-management role through liquidity facilities and large-scale interventions. This institutional layer helps the fiat phenotype survive shocks that would otherwise trigger runs and cascading failures.

• A structural bias toward positive inflation: In many jurisdictions, "price stability" is operationalised as a controlled erosion of purchasing power (often around 2% per year). This is a necessity for the survival of this monetary phenotype [3].

• Censorship and control capacity: Because fiat is administered through regulated intermediaries (banks, payment processors, and compliance frameworks), it is highly governable: digital funds can be frozen, transactions blocked and capital can be controlled.

In evolutionary terms, fiat demonstrated to have a very powerful phenotype, especially because of its adaptability: its parameters can be adjusted through institutional decisions rather than slow physical constraints. Yet the same traits that make fiat adaptable also introduce structural fragilities. Indeed, the fitness of the fiat phenotype correlates strongly with the quality and credibility of the issuing sovereign and with the sovereign's ability to extend demand for its currency beyond its borders. A concise illustration is the US dollar's post-Bretton Woods role in global commodity trade and reserve management: when critical goods (notably energy) are priced, financed, and settled in a particular unit, that unit gains an external "habitat" not confined to domestic tax authority (see petrodollar [4]). This creates persistent foreign demand for the currency and for its associated safe assets, reinforcing a feedback loop of network effects.

At the same time, fiat is not a single global species. There are roughly 160 fiat currencies, each with a local monopoly in its own jurisdiction, and most have little acceptance outside it. The global financial order is therefore closer to a managed, partially integrated barter system than a unified monetary world: cross-border life requires foreign exchange, correspondent banking, reserve assets, and political permission. A handful of currencies are held as reserves and enjoy meaningful foreign demand, but even these tend to lose purchasing power slowly over time. Most other currencies are more exposed to sharp devaluations, persistent periods of high inflation, and occasional hyperinflation, while enjoying little or no foreign acceptance. For households and firms, the practical implication is that saving in local fiat is often not a neutral act of prudence but a bet on institutional stability. In high-inflation environments, people rationally seek refuge in stronger foreign fiat units (often dollars) or in non-monetary SoV, and they frequently cannot rely on local banks to preserve purchasing power.

A recent IMF dataset of large depreciations since 1971 provides a useful empirical window into these "fitness crashes." It documents that large depreciations are more prevalent in lower-income countries and quantifies the frequency of major events: on average, a large depreciation episode occurred about once every 64 years in advanced economies, every 17 years in emerging markets, and every 15 years in developing markets [5].

Taken together, these observations support a sober conclusion: fiat money "won" because it solved the speed and scalability constraints that undermined gold-based standards in a telecommunications-driven world, but it did so by shifting monetary hardness into institutions. Where institutions are credible and fiscal capacity is strong, fiat can remain fit for long periods. Where they are not, loss of fitness tends to express itself through inflation, devaluation, banking fragility, and recurring crisis dynamics.

Crucially, even when a fiat currency collapses, most individuals do not escape fiat altogether. They typically fall back to a different fiat species, often the dominant reserve currency, or to the successor currency issued by the local sovereign. Yet the repeated, patterned nature of these failures has social and political consequences, and it shapes the environment in which monetary evolution continues. A monetary order built on discretionary elasticity and periodic resets predictably incentivises individuals to look for alternatives and motivates the development of monetary phenotypes that rely less on the credibility of any single issuer.

4. New Inflection Point: Money Becomes Digital

We are now witnessing a third major shift. While the internet allowed information to flow instantly and without gatekeepers, value transfer remained stuck in the previous era. Sending money still required centralized intermediaries, such as banks and payment processors. This created a massive unfulfilled incentive: to find a way to send value across the internet as easily as an email, without relying on a third party.

4.1 The Kill-Switch Problem

The core challenge was technical. Digital data is easy to copy, requiring a mechanism to prevent "double-spending". Early attempts like E-gold allowed digital transfers but relied on a central operator. When regulations tightened, these entities were shut down. Evolutionarily, centralized digital money had a "kill switch" that made it unfit for survival outside of state permission.

4.2 Bitcoin's Breakthrough

In October 2008, the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto circulated the Bitcoin white paper to a cryptography mailing list [6]; in January 2009, the open-source software launched and the first blocks were mined. The system combined earlier ideas (proof-of-work, timestamping, cryptographic validation) into a design that removed the central operator: a distributed ledger maintained by many independent participants. In addition, it introduced a way to settle a scarce digital unit over long distances without requiring trust in a custodian. This matters because the telecommunications era created a persistent asymmetry: transactions could move at "the speed of light, " while final settlement of scarce bearer assets (like gold) moved at "the speed of matter," encouraging layers of custodial abstraction and the debt-based financial superstructure.

In evolutionary language, Bitcoin resembles a novel monetary phenotype that can be selected for or against in different economic and political environments. Many of its traits echo the evolutionary advantages of gold, suggesting partial "inheritance" from the precious-metal lineage, while others are distinctly native to the digital age:

• Programmatic scarcity: Bitcoin is defined by a hard cap of approximately 21 million coins. The coin-issuance rules are hardcoded into the open-source protocol, ensuring a predictable supply that can only be altered through broad network consensus.

• Non-liability bearer asset: Ownership is not a claim on an issuer's balance sheet; Bitcoin can be hold in self-custody and does not rely on a bank's solvency.

• Permissionless access: Anyone can participate as a user; anyone can verify the ledger by running node software without asking permission.

• Censorship resistance: Transactions are broadcast and confirmed through decentralised validation rather than through a single gatekeeper.

• Portability and divisibility: Units can be stored as cryptographic keys and transferred globally; 1 Bitcoin is divisible into 100 million small subunits ("sats").

• Settlement and transparency: The ledger reaches probabilistic settlement as blocks are added every 10 minutes, and the monetary rule-set and history are auditable by participants.

• Layering potential: Like earlier monetary systems that grew layers atop base money, Bitcoin has accumulated higher-layer payment and custody patterns; some custodial, some not, to address usability and throughput constraints.

Applying the same functional lens used throughout this brief, Bitcoin's current fitness is mixed and path-dependent:

• SoV: Bitcoin's defining advantage as a potential store of value is rule-based digital scarcity. Its main disadvantage is price volatility measured in fiat currencies. This makes it difficult for entities with short time horizons or liabilities denominated in fiat.

• MoE: Bitcoin's base layer is not comparable to major fiat payment systems for high-volume retail throughput, and it is not usable for cheap "tap-to-pay" at global scale. When Bitcoin is used for payments, it is often in contexts that value traits other than convenience, such as reduced reliance on intermediaries. Scaling efforts tend to appear as additional layers (e.g. Lightning network), each with trade-offs.

• UoA: Almost nothing is denominated in bitcoin today. Wages, taxes, balance sheets and most contracts remain fiat-denominated, reflecting the incumbent advantage of sovereign monetary systems: taxation, accounting standards, and legal enforcement anchor the unit of account function.

A plausible evolutionary path, consistent with monetary history, is that a new monetary phenotype tends to establish itself first as a SoV, then (if price volatility and frictions decline and liquidity deepens) can expand toward MoE use, and only later, if it becomes sufficiently stable and widely used, might achieve UoA status.

4.3 The Cambrian Explosion

Once Bitcoin demonstrated that decentralised digital scarcity could persist and be exchanged, it inspired the creation of further monetary designs. The result resembled a Cambrian explosion: rapid experimentation with new "species" of money:

• Alternative cryptocurrencies (alt coins): Thousands of projects explored trait trade-offs relative to Bitcoin: higher throughput on the base layer, different governance systems, different security models, more expressive programmability, or more built-in privacy. Some were serious technical experiments; others were opportunistic, poorly governed, or outright fraudulent.

• Stablecoins: Stablecoins attempt to graft the UoA and low-volatility advantages of major fiat currencies onto crypto-native settlement rails. In evolutionary terms, they are hybrid organisms: they inherit stability from fiat anchoring while inheriting portability and programmability from digital networks, at the cost of new dependencies (reserve management, banking access, issuer governance, and regulation).

• Corporate private money experiments (e.g., Libra/Diem [7]): These projects sought to leverage platform network effects to create new payment instruments. Regardless of success or failure, they clarified that money creation can become contestable by large private actors when distribution, identity systems, and payment integration are already in place.

• Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs): Finally, Bitcoin acted as a catalyst for central banks to accelerate CBDC research and pilots. In design terms, CBDCs typically sit at the opposite end of the governance spectrum from Bitcoin: they modernise the sovereign ledger and may strengthen issuer control and policy transmission, potentially extending surveillance and programmability relative to today's bank-intermediated digital money.

From the Darwinian perspective, Bitcoin is therefore important even for readers who remain agnostic about its future. It did not merely introduce a new financial asset to speculate with; it introduced a new monetary phenotype and inspired a new design space for money; one that has already generated new private monetary instruments and new state responses aimed at preserving monetary sovereignty in an increasingly competitive environment.

5. Strategic Implications: Placing Your Bets

The return of monetary competition is not a theoretical abstraction; it is an active reality. The "monoculture" of the last fifty years is over, and we have entered a phase of rapid speciation. For the reader, this means the era of passive money management is ending. You must actively decide which "species" of money fits your environment now and in the future.

For investors and savers, the primary implication is the need to diversify monetary phenotypes. Holding only one type of money, typically a local fiat currency, exposes the holder to a single point of failure. Policymakers face a different challenge: they set the rules, but they cannot stop evolution. While regulations act as an environmental filter; potentially making it difficult for a new money to survive by blocking access points; history suggests that governments cannot easily kill a monetary trait that offers a massive survival advantage. If a local currency loses its fitness through high inflation or instability, value will inevitably migrate to a "fitter" species regardless of capital controls.

We cannot predict the ultimate winner of this evolutionary struggle, but we can identify the defining battles. Your strategy for the next decade will largely depend on how you answer three fundamental questions about the future environment:

• The trust question: institutions or code? The first bet is on the direction of institutional credibility. If you believe central banks will maintain or regain the discipline to protect purchasing power, then CBDCs and fiat currencies will likely remain dominant. However, if you believe fiscal pressure will force continued debasement, then "trustless" monies like Bitcoin will most likely capture a significant premium.

• The access question: permission or property? The second bet concerns the value of censorship resistance. In a stable environment, society tends to select for the efficiency and speed of centralized payments. But in times of conflict or polarization, the market places a premium on "unseizable" property. As geopolitical or domestic tensions rise, the utility of a bearer asset that cannot be blocked by a third party might increase disproportionately.

• The geopolitical question: alignment or neutrality? Finally, we must consider the structure of the global economy. In a fully globalized world, a single hegemon like the US Dollar acts as the apex predator. But if the world fractures into rival blocs, the fitness of "neutrality" rises. Nations and trade networks may increasingly prefer a reserve asset that no single adversary controls. While this trait has been dormant for decades, it may well be the decisive evolutionary factor of the coming years.

The answers to these questions will not be decided in a vacuum. They will be determined by the millions of daily selection decisions made by users, investors, and policymakers, each voting with their capital on which money is fit to survive in their respective environment.

References

- Lyn Alden: Broken Money: Why Our Financial System is Failing Us and How We Can Make it Better. Timestamp Press, 2023. Link

- Richard Nixon: Address to the Nation Outlining a New Economic Policy: 'The Challenge of Peace.' August 15, 1971. Link

- Luca Ferrarese: Inflation by Design, Deflation by Technology: Preparing for a Hybrid Monetary Order. SBI-004, 2025. Link

- Arya Joshi: How has the US maintained hegemony in the international oil trade through its control of the Middle East? The Journal of Global Faultlines. 2023. Link

- Alexander Culiuc and Hyunmin Park: Currency Crises in the Post-Bretton Woods Era A New Dataset of Large Depreciations. IMF Working Paper, WP/25/221, 2025. Link

- Satoshi Nakamoto: Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. White Paper, 2008. Link

- Ivan Pupolizio: From Libra to Diem. The Pursuit of a Global Private Currency. Global Jurist, 2021. Link